This article is about the activity of planning projects. If you are looking to design an education research project, the exercises on this page will help you. You might also look at Research Process Models to help you think about how research projects progress, or Iterative Design to think about to structure them for maximum likelihood of success.

If you’re doing video-based observational research, here’s a good companion piece to consider. If you’re thinking about Design-based research, check out this article.

More broadly, check out all articles tagged with “doing research”.

Key features for research projects

There are two key features of this approach that are tightly linked to research projects in specific.

Make space for emergence

Because research projects are designed to generate new knowledge, they necessarily have an element of discovery: we cannot know the outcome ahead of time. While we can often anticipate the shape of this new knowledge, discoveries along the way will prompt the emergence of new questions, methods, or analyses. This approach to planning projects explicitly makes space for emergence as a feature of research projects. As a corollary, it’s not great for projects where emergence is not desirable, such as when using backwards design to update a course.

Allow for flexible timelines

Research projects rarely have concrete intrinsic deadlines or end points. For example, if paper publication is a goal, researchers cannot predict how long a journal will keep a paper or whether they will need to resubmit or submit elsewhere. This approach to planning projects allows for flexibility in project timelines, because flexibility is often necessary in projects that generate new knowledge. As a corollary, there are better choices for planning projects with well-defined end points. A example project with a well-defined end point is your annual undergraduate research fair: you know when it is.

While you can use this approach for projects of any scope, it really shines for projects of duration 2-5 years and project teams of 2-10 people. I imagine that you’re using it for education research in a higher ed context, but it’s also amenable to other contexts and allied fields.

A quick note on terminology

Research design and project planning are entangled activities. They’re both important, but different. This article is mostly about how they are entangled, not how to intellectually align the elements of your research project. Relatedly, I use these phrases in my work: “research design” (a thing) vs. the “research design process” (a mechanism to make a research design) vs. “research process” (how research is done).

There is a little ambiguity around the phrase “planning projects”.

- “Planning projects” (thing): a project whose job is to plan a bigger project (e.g. capacity building, consensus seeking, community needs analysis)

- “Planning projects” (activity): the activity of planning a specific project.

This article is about the activity of planning projects.

Phases of a research project

As you plan your project, you will go through three major phases:ideating,planning, andexecuting.`

In the ideation phase, your major goal is to develop the idea for the project: what is the big problem you want to solve? what’s your central research question?

In the planning phase, your major goals are to develop a research design that’s aligned with your available resources and a project workplan or timeline that includes iteration and makes space for emergence.

In the execution phase, your major goal is to do the project, updating the design and timeline as new ideas and opportunities emerge. In this article on planning and ideation, I’m not going to focus on execution.

In all of these phases, you will spend a lot of time documenting what you do and why; communicating with your team, your mentors, and the broader research community; and iteratively refining and updating your ideas. While I’ve presented these phases as if they are sequential and separate, a lot of the activities overlap. You might find yourself returning to the ideation phase, especially if something very cool or very concerning has just emerged in your project execution. This is normal. However, it’s valuable to be intentional about what phase you are in and what you’re trying to do.

You might find it helpful to read generative writing and research process models before you get started; if this feels really comfortable to you and you want to look deeper, check out how iteration, generation, and reflection are baked into my research process. If you’re ready to build an iterative design, read the next article in this series.

Ideate

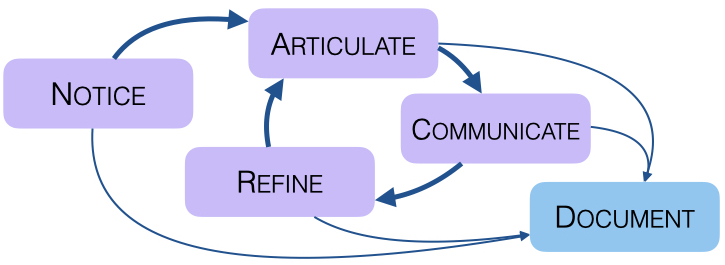

In the first phase of project planning, you don’t even have a project yet. You are working to figure out what kind of knowledge you want to generate or what kind of problem that you want to solve. There are five major activities here:

- Notice a problem OR spark a curiosity

- Articulate: what’s the problem? what happened that made me curious?

- Communicate: talk to stakeholders, read literature, talk to other researchers / peers / mentors

- How do they frame this problem / question? what are some elements of solutions?

- What’s the local context for how this problem or question is situated?

- Refine: what’s the big problem I want to solve? what’s is my overall research question?

- what’s the character and scope of the knowledge I want to generate in this project?

- what are my major values or vision, and how does this project help move them forward?

- Document: generative writing will help you corral, elaborate, and refine your ideas.

This phase can be a little sneaky: if you’re in the habit of being broadly interested, you might find that your curiosity sparks easily and you are constantly awash in possible ideas to pursue. You might be really practiced at noticing problems in your classes or your programs. If you play “yes, and” with all the papers you read and the people you meet, you could be constantly surrounded by opportunities to ideate new projects. You might accidentally fall into this phase for a new project without meaning to, and that’s ok. For you, the essential work of this phase is about refining one big idea out of your soup of opportunities. You don’t have to fit all of your interests into one project. It’s ok to save some for later.

Alternately, you might need to be deliberate about getting started in a new project. Maybe you have an external target in mind, like earning a PhD or writing a grant proposal. It can be hard to generate a new project on demand. You might struggle with feeling like you don’t have any ideas that are “big enough” to fit the size of your target, or that all of your ideas are too big for your target. This is normal. For you, the essential work of this phase is about communicating and refining your ideas so that their scope and intent is well-aligned with the needs of your external target.

Plan

As you plan your project, it starts to take shape. In this phase, you’re working to figure out what you want to do and how you want to do it. Some projects require you to be very intentional in this phase, especially if you are writing a grant or thesis proposal. Other projects can evolve more organically over time, and you might start a formal planning process after work has already occurred, or need to restart a planning process when the project experiences a major pivot.

Formalize your project

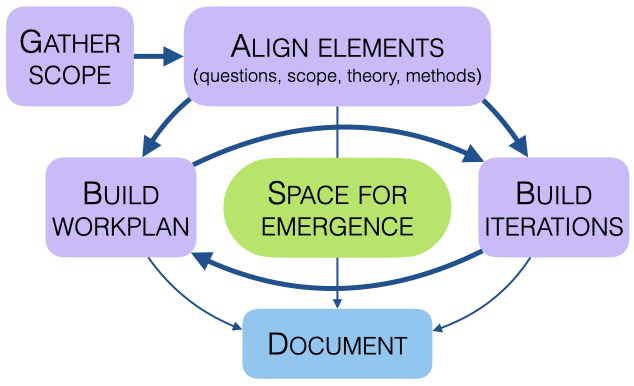

The major activities in this phase are:

- Gather your scope / resources: how long? how much money? what access? which partners? which mentors? Talk to stakeholders & partners about this, and develop your scope in conversation with them.

- Align question, scope, methods, theories to match well with each other. Some people think the product of this process is your “research design”: an intellectual product that shows how your ideas connect together.

- Build in iterations and space for emergence: what’s the major knowledge milestone for each piece? How do they build together? This activity blends between building a research design and project planning. While smaller projects might not need a lot of iteration, generally speaking it’s a wise choice to plan for iteration in many different time scales. Some people think that the product of this process is the “research design”: a roadmap for how to enact the intellectual product you defined in the alignment activity.

This activity blends between building a research design and project planning. While smaller projects might not need a lot of iteration, generally speaking it’s a wise choice to plan for iteration in many different time scales. Some people think that the product of this process is the “research design”: a roadmap for how to enact the intellectual product you defined in the alignment activity.

Make a workplan

After you gather your scope, align your project elements, and build in iteration, you need to make a project workplan or timeline, including contextual constraints as appropriate (course schedules, submission deadlines, staffing, etc)

- If there are dependencies, identify them.

- Build in some buffers, especially around a critical path.

- Identify risks and make a plan to mitigate them

- Be realistic about your capacity and check in with your stakeholders about theirs

- Don’t over specify this timeline, especially for later iterations or for work other people should do.

Building a project workplan is classically considered “project planning”, not research design.

Document your plan

Document what you plan, why, and when so that you don’t forget and so that you can notice if your plans change. Your documentation can take several forms, but it’s nice to keep it in a central place where all project members can access it. If part of your project entails writing a thesis proposal or a funding proposal, then parts of this documentation might make it into your proposal documents. However, you probably have more detail in your internal documents than fits into your formal proposal.

Execute

Do your project, iteratively. Realistically, over the lifetime of a project, you should spend most of your time in this phase.

However, you should also plan to return to the ideating and planning phases regularly once you have started executing. Plan to return to planning as you start each iteration and regularly within to let your project breathe and grow. Plan to debrief, reflect, and document regularly and as you finish each iteration. This will help you attend to how your project develops, make sure it’s aligned with your (developing) goals, and learn new process knowledge about how to do this kind of work.

Don’t mistake planning to do a thing for actually doing the thing. If you find yourself in endless cycles of planning and documentation, but don’t move forward on actually doing the project, it’s time to take a step back and ask yourself if this is really a project you want to engage with at this time.

Make space for emergence

As you engage in research, you will learn new things. The act of mindfully noticing will spark new ideas about avenues to pursue in data collection or analysis. Reading papers will suggest new theories to try or new ways to frame problems and solutions. Chatting with colleagues and coordinating with your collaborators will expand the space of possibilities for research questions and designs. New opportunities and constraints will occur in your research setting, and there will be unanticipated events that you have to react to.

All of these factors can contribute to the emergence of new ideas and directions for research. Emergence is the process of something coming into being or becoming important. In science, emergence is when a wholly new behavior or property occurs out of the collective action of interacting parts. The flowing shapes of a murmuration of starlings are an emergent phenomenon. Traffic jams are emergent. Emergence is a common feature of research projects, and it can be beautiful.

You can’t plan exactly in advance what new ideas and opportunities will emerge in the course of your research project. However, you can anticipate the character of what they might be, and build space in your research plan to foster opportunities and mitigate risks.

As you make space for emergence in your research plan,

- Use an iterative design to get data that will help you make decisions in the next iteration.

- Plan to check in regularly with stakeholders, external evaluators & research community.

- If there are go/no go decision points, identify them.

- Remember that it’s ok if your plans change.

Planning for emergence is what separates this process from classical project planning, which treats changes as risks to be minimized and mitigated.

Additional topics to consider

Want more?

This book is a labor of love, but alas love doesn’t pay the bills and I don’t have a day job. I would be delighted to give a workshop about the topic of this chapter – or any other chapter(s) – for your group. Please contact me for more details.

History

This article was first written on May 1, 2023, and last modified on July 18, 2025.