Who decides if your research is ethical?

You, but not only you.

There’s lots of interesting (and disturbing) history that led to regulations in how research with human subjects can be conducted ethically. In the US, these regulations are contained within the Common Rule, 45 CFR part 46, via the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Colloquially, these regulations are also known as the “IRB regulations” because the part of your institution which reviews proposed research projects for compliance is called the Institutional Review Board, or IRB. Every institution has their own IRB, and all IRBs abide by the federal-wide regulations in 45 CFR part 46.

Additionally, the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (“FERPA”) governs who can use students’ educational data and for what purposes. Generally, there are two carveouts in FERPA: one for legitimate educational purposes (you’re allowed to see your own students’ work for grading purposes, for example); and one for research, but the details matter. Your IRB does not check for FERPA compliance; that’s your university lawyers. This article is not legal advice, I am not a lawyer, and I am definitely not your university’s lawyer. However, generally speaking, for most education research projects, you don’t need to worry about FERPA.

This article focuses on the US regulations. While the principles of ethical research with humans are universal, these regulations are special to the US context.

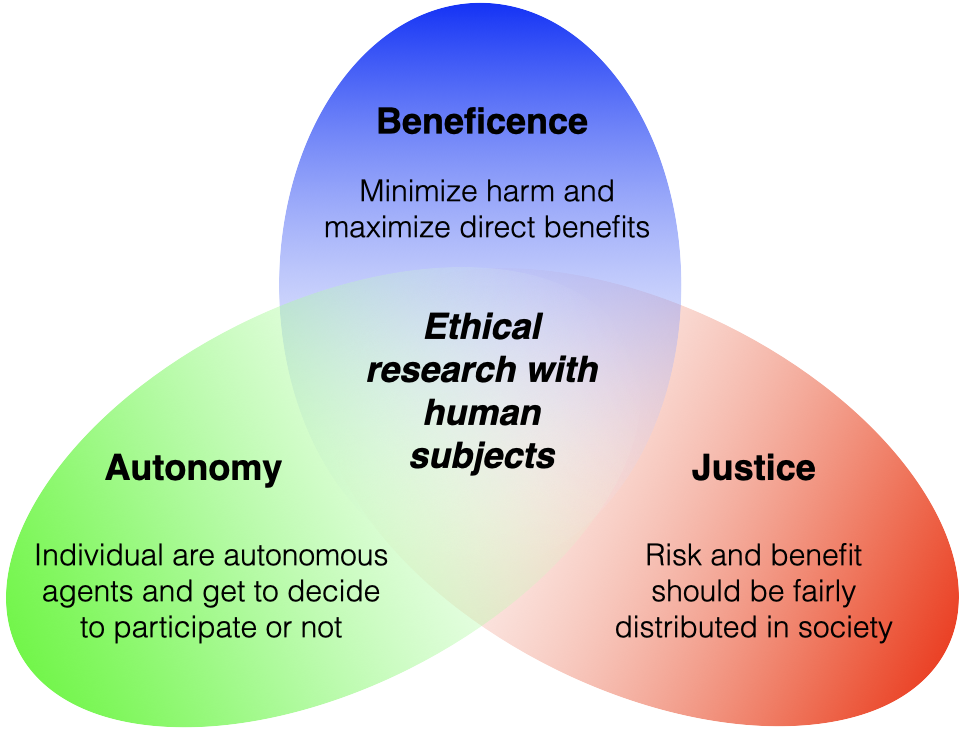

Principles of Research with Human Subjects

Conducting research ethically is important at all stages of the research process: when you’re designing your project, when you’re collecting your data, when you’re analyzing it, when you’re preparing your work for publication, and when you’re hanging out in the hallway with your research team.

Autonomy/Respect for Persons

We should respect individuals as autonomous agents:

- Persons have the right to decide whether or not to participate and can decline/withdraw without penalty (no undue influence).

- Participants must know and understand the risks and benefits and be informed if these change.

- Individuals with diminished autonomy should be protected.

Beneficence

We should protect others from harm and work to secure their well-being

- Do NO harm and minimize possible harms

- Maximize possible direct benefits

- Inform participants of potential risks and benefit

- Include voices from participant demographics in determining potential harm from results, methods, questions, and researcher.

Justice

Risk and benefit should be fairly distributed in society

- Do not exclude based on age, race, gender, etc. without strong reason

- One group should not bear the risk for which another group benefits

- If possible, participants should be randomly assigned treatments so risks and benefits are equally distributed

The responsible conduct of research is not just about conforming to applicable regulations. For all work with human participants, their consent to participant should be informed, explicit, and on-going.

As a researcher, your work must

- fairly and accurately represent your processes and your findings

- engage in a scholarly conversation with attribution

- include reasonable safeguards to protect data security and scientific integrity

- partner with the communities in which it occurs and who may be affected by it

- treat members of your research team and community as full humans

If you hold multiple roles, such as researcher and instructor, you need to make sure that student information that you learned as an instructor does not leak into your research, and student information that you learned as a researcher does not leak into your classroom activities.

Jack is conducting classroom observations in an introductory calculus class to learn about student understanding of function and derivative. Two students in the class discuss in detail their plans to cheat on the next exam. Based on their conversation, he suspects they cheated on the last exam. Jack has their conversation on video, and he also has copies of their last exams which covered his research topic.

What should Jack do? Think about:

- academic honesty

- scientific integrity

- data analysis.

Do you need IRB review? What kind?

Every institution has their own IRB to handle research on their students and faculty. As you think about your project and get started with your IRB, these are the first questions to ask:

Is it research?

Is your project a systematic investigation designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge?

Evaluation is not research, and generally you don’t need IRB approval to conduct an evaluation of your teaching or program. The difference between evaluation and research can be subtle. Read more at Evaluation and Research

Does it involve human subjects?

Does your project involve living individual(s) about whom the investigator obtains information through intervention or interaction with the individual OR identifiable private information and uses, studies, or analyzes the info.

If your project is about developing a curriculum, the curriculum development is not research with human subjects.

If your answer to either question is “no”, then your project does not need to be reviewed by your IRB. However, details matter. Talk to someone in your IRB office before you get started. It’s their job to make these decisions.

If your answer to both questions is “yes” or even just “uh, I think so?”, then you need to file paperwork and go through IRB ethics training through your institution.

Some people think that the intent to publish is what distinguishes research and evaluation, but that’s not accurate. The actual distinction is not about whether you want to publish your work; it’s about what kind of knowledge you intend to generate. Read more at Evaluation and Research

Also, if you decide you want to use data for research later, changed intentions do not mean you can avoid IRB approval.

Rory has been teaching upper-level quantum mechanics for several years and always scans written homework, quizzes, and exams for their records before grading them. They have decided that they would like to use this written work to explore what resources students bring to quantum mechanics in order to design activities to build on these resources. They hope to publish their findings in The Physics Teacher so other instructors can also benefit from their work.

- What questions/issues might Rory have for their IRB?

- What are the issues that Rory should attend to in their paperwork?

What kind of review?

| Kind of Review | Why? | Timing |

|---|---|---|

Full Board Review |

Most extensive paperwork for projects that involve substantial risk or protected populations | Reviewed by the full IRB so takes the longest time |

Expedited Review |

Non-exempt research with minimal risk. Same paperwork as full. | Reviewed by a sub-committee of the IRB so less time for review. |

Exempt from further review |

Research must be eligible for exemption in a specific category. Still requires paperwork, but it is much less extensive. | Reviewed by single IRB member so much less time. |

Non-reviewable |

No paperwork, but it is a good idea to verify that your research is non-reviewable | Check with your IRB, but generally quite fast. |

The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has some really excellent decision charts. You should use them to decide whether your project is covered by these regulations, what kind of review is required, and what additional documentation might be necessary.

IRB Process

Broadly speaking, here’s the regulatory process for doing research with human subjects:

- Before you propose your project:

- Do IRB ethics training (e.g. via the CITI program), as specified by your institution.

- Decide what you want to do in concert with guardians of your population (this may include some non-research pilots)

- Satisfy three principles

- Ask the IRB if you can do it and wait for their approval

- Lots of paperwork

- If you think your project may be

exempt, you specify which (if any) exemption category or categories you believe apply and IRB decides whether the research is exempt - Timing and feedback varies significantly by institution and discipline

- Do the work.

- Don’t deviate from your approved procedures.

- File an amendment if you want to change procedures, add researchers, or extend your study

- Report adverse interactions.

FAQ

There are independent IRBs that researchers can submit their projects to. Some institutions contract with them at the institutional level, and some researchers work independently with them. Even if you don’t have an IRB in-house, you still have access to an IRB.

Great! There are two common choices here.

If you have a partner at that institution, they can apply for IRB approval. Depending on their IRB and what you want to do, they can add your name to their application as an external researcher, or you can apply to your IRB to use their data (and include their application in your materials).

If you do not have a partner at that institution – or you’re looking to do a study with people who might be at a large number of institutions – you might also be able to apply only at your own institution.

Talk to your IRB (and your partner’s IRB, if applicable) to see what they recommend for your project in specific.

Uh, sure. It’s really common for emerging education researchers to want to model their applications on successful applications from other schools.

However, every institution has different forms for IRB applications. My forms are going to look a lot different from your forms. A better use of your time is to find someone at your institution and model on their forms. If you don’t know anyone, start with the chair of the Psychology Department or the chair of the IRB.

Because each institution has their own IRB, each institution can interpret the rules slightly differently. These differences are most apparent when figuring out if education research is exempt or expedited, when estimating how long the approval will take, and when handling researchers from multiple institutions.

They’re probably both right. Don’t fight your IRB. Talk to them about what you want to do and what documentation they need from you, then do what they say.

As part of interacting with research subjects (current and potential), researchers are required to share (a) that they are doing a research study; (b) what they’re doing; (c) who their IRB is; and (d) how to contact their IRB. If you have this information – or you know what institution they’re at so can look up their IRB – you are allowed to contact their IRB. It’s ok. Ask about what the researcher is doing and why. The IRB exists to protect you, the (potential) research subject. It’s the IRB’s job to figure out what’s hinky.

If you don’t want to contact the IRB directly, you can ask the researcher. If they’re not in charge of the research project, they can direct you to the person in charge. If they are in charge, they can – and should – answer your questions about the project with enough detail to help you decide if you want to participate.

Talk to your IRB. No really, talk to them. Their central concerns are (a) researchers do ethical research and (b) nobody does unnecessary or incorrect paperwork. It is literally their job to decide which paperwork you need to file, and then process your paperwork.

- They do not want to receive bad paperwork, because that’s more work for them to process and you to refile appropriately.

- They do not want you to skip necessary paperwork, because that’s unethical and also creates more complicated paperwork later.

Especially if your project is large or complex, or if you are new to education research, or if you are new to your institution, it is ok to talk to your IRB about how to do your research ethically as well as what paperwork to file.

Additional topics to consider

Want more?

This book is a labor of love, but alas love doesn’t pay the bills and I don’t have a day job. I would be delighted to give a workshop about the topic of this chapter – or any other chapter(s) – for your group. Please contact me for more details.

History

This article was first written on May 3, 2023, and last modified on April 4, 2025.