Research: A Practical Handbook

This handbook is about the practice of research, particularly education research, and particularly in higher education in the US. These chapters:

- make tacit professional knowledge more explicit, particularly around fundamental practices of research;

- are short, friendly, and have actionable exercises;

- support a wide range of people to become better at their work: students just getting started, new faculty, venerable advisors, casual researchers, and postdocs conceptualizing their first independent research.

The practical fundamentals of doing research are widely applicable across a vast majority of research projects. Some of these practical fundamentals are centered on education research, while others are broadly applicable across many fields of research. I try to balance broad coverage with brevity.

The table of contents for this handbook suggests a reading order:

Part 1: Getting Started contains three core chapters about fundamental skills and perspectives which shape this handbook and the practice of doing research.

Part 2: Research Design features four core chapters about research design and project planning, from the intellectual work of building a coherent research project to the logistical work of figuring out how to do it. Following the core chapters, there is a selection of other articles which expand on particular elements of research projects (like methods and theories), and which compare research projects to other kinds of projects in education.

Part 3: Writing focuses on writing, a fundamental skill from Part 1. The core chapters in this section address how writing is an integral part of your project, while the additional articles at the end expand on different aspects of writing as a part of research and research communication.

Part 4: Research with People takes up the principle that research is done with teams and in communities, and that education research in specific often has human participants. Following the core chapters, there is a selection of other articles which expand on mentoring, team work, and ethics of research with human participants.

At the end, there are more resources:

- Case studies, a list of all the case studies used in this handbook, linked to the articles in which they appear.

- Readers’ Guide, three more tables of contents for this handbook, sorted by what kind of reader you are: faculty, student, or PEER participant.

- All articles, a full chapter list all the articles in this handbook, with categories.

- Frequently Asked Questions, the FAQ, with answers to your questions about the process of writing this handbook and the future of its development

You are encouraged to read whichever chapters seem appealing to you, in whatever order you desire. If you’re curious about just getting started, start at the top and see where it leads you. Alternately, if you are faculty, a student, or a PEER participant, I have already tagged which chapters are most likely to appeal to you.

What is research?

Research is a process of generating new knowledge for the scientific community; education research focuses on questions of teaching and learning. Generally speaking, projects whose only goals are to teach the participants (e.g. class projects) or evaluate a class or a program (i.e. evaluation) are not research projects because the knowledge generated is not new to the scientific community.

We gauge the success of research on whether other scientists think it’s novel and well-executed. There are lots of ways to judge novelty or execution, but all of them hinge on other people in the community knowing the results and how they were developed. If you hoard your results away from everyone else, you’re not doing research.

Research can be fundamental or use-inspired. In education, use-inspired research often tries to do good in the world (e.g. by helping more people learn more), while fundamental research tends to be driven by curiosity without a direct need for immediate impact.

Research is fun, mostly. There are parts that are tedious and boring, like transcription or washing the glassware. There are parts that are frustrating, like when your participants don’t participate or your code is broken. But, in a deep and fundamental sense, the practice of research is fun and exciting.

Research is creative, mostly. There are parts which are routine and repetitive, like checking your journal formatting or applying a developed protocol repeatedly. However, in a deep and fundamental sense, the act of doing research is about imagining something new, creatively seeking a solution or discovery, and documenting what you do and why.

Research is a human endeavor. People do research collaboratively in groups. Research is more fun when you’re doing it with people you want to work with. They can be local to you or remote, but either way you should communicate often. While some kinds of research require a team, other kinds of research don’t.

Altogether, a successful research program generates new knowledge, brings together multiple people in different roles, and is usually fun for the research team.

A research program is made up of a bunch of inter-related research projects. While each project might be long or short, the program last over many years. Most research programs have a lot of projects which never succeed: maybe the data were flawed, or the theory was insufficient, or the person doing the analysis kept bad notes and graduated early, or whatever. You should seek to minimize the number of unsuccessful projects, but recognize they will exist. About half of mine are unsuccessful.

Who is this handbook for?

This handbook is for you.

Generally, people learn how to do education research as students, postdocs, or faculty members. Most newcomers to the field start with a mentoring relationship with another researcher. We call these scholars emerging education researchers. Because most of them are situated in disciplinary departments, we also call them “emerging discipline-based education researchers”, or EDBERs. As a research mentor, I wrote these articles because my students and junior colleagues needed them.

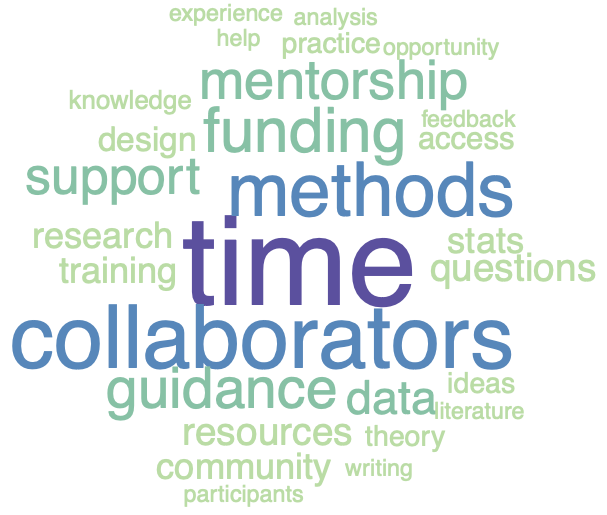

In education research, there are also a lot of people who get started without a direct mentor. As faculty, they might be focused on improving the learning or success of students in their departments; as learners themselves, they might seek to improve learning more broadly for people like them. They might get started by participating in a field school, workshop, or conference. They might transition into education research as a natural extension of their other professional duties, like teaching, running an outreach program, or evaluating programs at their institution. As someone who works with emerging education researchers, I wrote these articles because people kept asking: what’s a good overview of…? how do I…? can you help me learn to…?

If you’re looking to get started or broaden your experience in STEM education research, you might also be interested in PEER field schools for emerging researchers. Many of the articles in this handbook grew from my work with PEER, and PEER uses them extensively in our workshops and field schools. I would love to bring PEER to you. Contact me for more details about how.

Limitations

There are always edge cases where this advice won’t fit. This handbook can’t possibly handle everything for every project. As your questions and curiosities become more specialized, you’ll want to look for more specific resources.

Also, the practical fundamentals of doing research are independent of the particular tools you use to instantiate your research, so this handbook is not about particular software tools.